Over the last dozen weeks I've surveyed some of the high points in the development of etheric technology in the Western world from Mesmer to Hieronymus. That's not the whole story by any means, of course. Many other researchers also noticed that there seems to be some form of energy, or something similar to energy, that is generated or concentrated by living things, and can be used for purposes of healing on the one hand and expansion of consciousness on the other. That was not a new discovery when Mesmer made it. What set him and the other figures in this sequence of posts apart from many others is that he, and they, set out to work with this energy using Western civilization's strong suit -- its mastery of machines.

Over the last dozen weeks I've surveyed some of the high points in the development of etheric technology in the Western world from Mesmer to Hieronymus. That's not the whole story by any means, of course. Many other researchers also noticed that there seems to be some form of energy, or something similar to energy, that is generated or concentrated by living things, and can be used for purposes of healing on the one hand and expansion of consciousness on the other. That was not a new discovery when Mesmer made it. What set him and the other figures in this sequence of posts apart from many others is that he, and they, set out to work with this energy using Western civilization's strong suit -- its mastery of machines. A case can be made, and of course it has been made at great length and with quite some force, that our civilization's focus on building machines rather than developing human capacities is the source of many or most of our problems. That's a valid view, and the old joke about the five-year-old with the hammer who thinks everything is a nail is relevant here. That said, machines are something we're good at, and while it's worth putting energy into encouraging people to develop their own etheric capacities, I don't think it's a mistake for us to tinker with etheric machines as well -- especially when those machines appear to have significant capacities for healing and personal transformation.

One thing I find fascinating about all of this is that the development of etheric technology has followed the usual course of an emergent science, not that of a religious or mystical belief system. One of the distinctive features of a science is that once the initial paradigm is in place, its development is cumulative: it starts with initial hypotheses and experimental procedures that are relatively simple and tentative, and builds on those, discarding hypotheses that don't work while retaining those that do, and gradually buildng up a body of technique that allows similar results to be obtained reliably by different practitioners irrespective of personal qualities. Religions and systems of mysticism don't usually do this, but radionics has done so.

One thing I find fascinating about all of this is that the development of etheric technology has followed the usual course of an emergent science, not that of a religious or mystical belief system. One of the distinctive features of a science is that once the initial paradigm is in place, its development is cumulative: it starts with initial hypotheses and experimental procedures that are relatively simple and tentative, and builds on those, discarding hypotheses that don't work while retaining those that do, and gradually buildng up a body of technique that allows similar results to be obtained reliably by different practitioners irrespective of personal qualities. Religions and systems of mysticism don't usually do this, but radionics has done so. Mesmer's basic theory, which he derived from earlier writers and researchers, has on the whole turned out to be broadly correct, but significant parts of it have been jettisoned and more have been refined. Meanwhile, the technology has developed in an equally cumulative fashion. Mesmer's baquets made use of the curious fact that etheric energy in some contexts behaves like electricity -- it can be made to flow through conductors, and it can be controlled and modulated by means of something closely parallel to capacitance and resistance. The same thing is true of radionics today. From Mesmer all the way to the latest variation on the Hieronymus machine or the high-end radionics gear used by British practitioners, the same principles apply, but they are put to use with increasing precision and subtlely.

And now? Radionics is a flourishing field these days; go online and you can find scores of websites where people are working with the machines pioneered by Drown, Reich, and Hieronymus, and there's noticeable interest in some of the others. (I haven't yet seen anyone building a Mesmeric baquet, but with any luck it's just a matter of time.) The collapse of public confidence in the modern medical-industrial complex is accelerating, and so is the parallel dissolution of widespread acceptance in the dogmatic materialist paradigm of todays corporate scientific establishment. There are good reasons for both these shifts, of course. A medical system that has by and large given up curing people, because it's more lucrative to keep them sick and "manage" their conditions, has no one but itself to blame if patients go elsewhere, just as the proponents of an ideology that can only be defended by demanding that people ignore an ever-growing share of their own experiences are going to be disappointed if they think they can expect blind faith in their pronouncements.

And now? Radionics is a flourishing field these days; go online and you can find scores of websites where people are working with the machines pioneered by Drown, Reich, and Hieronymus, and there's noticeable interest in some of the others. (I haven't yet seen anyone building a Mesmeric baquet, but with any luck it's just a matter of time.) The collapse of public confidence in the modern medical-industrial complex is accelerating, and so is the parallel dissolution of widespread acceptance in the dogmatic materialist paradigm of todays corporate scientific establishment. There are good reasons for both these shifts, of course. A medical system that has by and large given up curing people, because it's more lucrative to keep them sick and "manage" their conditions, has no one but itself to blame if patients go elsewhere, just as the proponents of an ideology that can only be defended by demanding that people ignore an ever-growing share of their own experiences are going to be disappointed if they think they can expect blind faith in their pronouncements. As Yogi Berra famously said, prediction is tough, especially when it's about the future. My sense, though, is that etheric technologies may be approaching an inflection point of a kind well known in the history of science, a stage at which many tentative ventures with promising results come together in a new synthesis that sparks a burst of innovation. That could open up fascinating possibilities, by itself and in conjunction with the ongoing exploration of Western esoteric spirituality and occultism. Still, we'll see.

While George and Marjorie de la Warr were putting radionics on a sound footing in Britain, and Meade Layne was beginning the process of synthesizing the work of earlier etheric researchers into a general theory, more developments were under way in the United States. One of the most influential figures in that process was the American electronics engineer Dr. Thomas Galen Hieronymus, the inventor of the Hieronymus machine and several other significant advances in radionics technology. Yes, that's him on the left.

While George and Marjorie de la Warr were putting radionics on a sound footing in Britain, and Meade Layne was beginning the process of synthesizing the work of earlier etheric researchers into a general theory, more developments were under way in the United States. One of the most influential figures in that process was the American electronics engineer Dr. Thomas Galen Hieronymus, the inventor of the Hieronymus machine and several other significant advances in radionics technology. Yes, that's him on the left.  He had a lifelong interest in new electronic discoveries, and that was what got him involved in radionics. By 1930 he was working with J.W. Wigelsworth, one of the many radionics practitioners active in that era, on a version of Albert Abrams' machine that made use of the dramatic advances in electronic technology in that era. The Pathoclast, the machine developed by Hieronymus and Wigelsworth, came to be widely used all over the United States, and was adopted by some mainstream doctors as well as by homeopathic physicians, who found it especially well suited ot their needs.

He had a lifelong interest in new electronic discoveries, and that was what got him involved in radionics. By 1930 he was working with J.W. Wigelsworth, one of the many radionics practitioners active in that era, on a version of Albert Abrams' machine that made use of the dramatic advances in electronic technology in that era. The Pathoclast, the machine developed by Hieronymus and Wigelsworth, came to be widely used all over the United States, and was adopted by some mainstream doctors as well as by homeopathic physicians, who found it especially well suited ot their needs.  That, in turn, was what brought it to the attention of John W. Campbell, the editor of Astounding Science Fiction, one of the iconic SF magazines of the era. Many science fiction fans these days like to pretend that their genre has always been obsessed with the same sort of crackpot rationalism that so often infests it these days, but that's an act of revisionist history that would have made Stalin drool with envy. Go read 1940s and 1950s science fiction magazines -- there are plenty of them online these days -- and you'll find that the stories in them are chockfull of psychic phenomena, mysterious powers, lost civilizations, mystical notions: you know, all the stuff that today's rationalists hate most. The classified ads in back were usually well stocked with mail order occultism courses and books on weird phenomena.

That, in turn, was what brought it to the attention of John W. Campbell, the editor of Astounding Science Fiction, one of the iconic SF magazines of the era. Many science fiction fans these days like to pretend that their genre has always been obsessed with the same sort of crackpot rationalism that so often infests it these days, but that's an act of revisionist history that would have made Stalin drool with envy. Go read 1940s and 1950s science fiction magazines -- there are plenty of them online these days -- and you'll find that the stories in them are chockfull of psychic phenomena, mysterious powers, lost civilizations, mystical notions: you know, all the stuff that today's rationalists hate most. The classified ads in back were usually well stocked with mail order occultism courses and books on weird phenomena. Campbell's editorials and a flurry of other pieces pro and con attracted a fair amount of attention in various corners of American society, but soon other things caught the public interest. Other than that brief brush with notoriety, Hieronymus continued his researches until just before his death in 1988. Having learned from the dismal fates of Ruth Drown and Wilhelm Reich, he was exquisitely careful not to do anything to draw down the wrath of the medical industry; he never publicly claimed to cure anything, and his publications on radionics present it as an experimental technology and earnestly warn readers not to use it in place of an established treatment. Of course everyone involved recognized that as the legal dodge it was, and radionics treatment thrived as an underground healing modality all through the second half of the twentiety century.

Campbell's editorials and a flurry of other pieces pro and con attracted a fair amount of attention in various corners of American society, but soon other things caught the public interest. Other than that brief brush with notoriety, Hieronymus continued his researches until just before his death in 1988. Having learned from the dismal fates of Ruth Drown and Wilhelm Reich, he was exquisitely careful not to do anything to draw down the wrath of the medical industry; he never publicly claimed to cure anything, and his publications on radionics present it as an experimental technology and earnestly warn readers not to use it in place of an established treatment. Of course everyone involved recognized that as the legal dodge it was, and radionics treatment thrived as an underground healing modality all through the second half of the twentiety century.  In the nine previous posts in this series, we've talked about a disparate assortment of technologies, all of which seem to relate in various ways to the realm of being that traditional occultists call the etheric plane: the plane of the life force. Mesmer's "animal magnetism," Reichenbach's "od," Eeman's "X force," Kilner's "human atmosphere," Reich's "orgone," and the strange resonances and reactions explored by Abrams, Drown, the de la Warrs, Tansley, and others all seemed to be aspects of the same polymorphous life force. As usually happens in the early phases of any scientific investigation, however, most of these researchers pursued their work in relative isolation from one another. The rise of radionics technology was the one chief exception to that rule -- Ruth Drown picked up where Albert Abrams left off, and Drown's work inspired the later radionicists -- but even so, not until David Tansley's time did that current of exploration start to draw significantly on the broader body of etheric research.

In the nine previous posts in this series, we've talked about a disparate assortment of technologies, all of which seem to relate in various ways to the realm of being that traditional occultists call the etheric plane: the plane of the life force. Mesmer's "animal magnetism," Reichenbach's "od," Eeman's "X force," Kilner's "human atmosphere," Reich's "orgone," and the strange resonances and reactions explored by Abrams, Drown, the de la Warrs, Tansley, and others all seemed to be aspects of the same polymorphous life force. As usually happens in the early phases of any scientific investigation, however, most of these researchers pursued their work in relative isolation from one another. The rise of radionics technology was the one chief exception to that rule -- Ruth Drown picked up where Albert Abrams left off, and Drown's work inspired the later radionicists -- but even so, not until David Tansley's time did that current of exploration start to draw significantly on the broader body of etheric research.  He combined his academic work with a lively interest in occultism, and studied with Crowley's errant disciple Charles Stansfeld Jones as well as with Israel Regardie and William Wallace Webb; his 1945 booklet The Art of Geomancy shows an extensive knowledge of Golden Dawn occultism. (Golden Dawnies will also want to take a close look at the version of the caduceus on the image to the right.) He was also an active contributor of papers to the American Society for Psychical Research and the Fortean Society.

He combined his academic work with a lively interest in occultism, and studied with Crowley's errant disciple Charles Stansfeld Jones as well as with Israel Regardie and William Wallace Webb; his 1945 booklet The Art of Geomancy shows an extensive knowledge of Golden Dawn occultism. (Golden Dawnies will also want to take a close look at the version of the caduceus on the image to the right.) He was also an active contributor of papers to the American Society for Psychical Research and the Fortean Society. In terms of the story we're following, however, the most important aspects of BSRF's work had nothing to do with flying saucers. Among the core interests of the Foundation's members was anything relating to the etheric plane and the life force that pervades it. Articles on Albert Abrams' and Ruth Drown's research into radionics thus found their way into the Round Robin and its successor the Journal of Borderland Sciences; so did articles on Leon Eeman's screens; so did many other related subjects, including new investigations such as Project VITIC, which explored the effects of magnets and carbon rods on the human energy field and demonstrated that these effects could be measured using magnetometers.

In terms of the story we're following, however, the most important aspects of BSRF's work had nothing to do with flying saucers. Among the core interests of the Foundation's members was anything relating to the etheric plane and the life force that pervades it. Articles on Albert Abrams' and Ruth Drown's research into radionics thus found their way into the Round Robin and its successor the Journal of Borderland Sciences; so did articles on Leon Eeman's screens; so did many other related subjects, including new investigations such as Project VITIC, which explored the effects of magnets and carbon rods on the human energy field and demonstrated that these effects could be measured using magnetometers.  The most influential of the second generation of British radionics researchers was the husband-and-wife team of Marjorie and George de la Warr. (That's Marjorie on the right, working with one of their radionics machines.) George was an engineer who became fascinated with radionics between the two world wars. At that time nearly all radionics gear was manufactured in the United States, and getting the necessary equipment overseas was expensive. De la Warr's response was to contact Ruth Drown and get a license to build machines using her design in Britain. De La Warr Laboratories soon became a major supplier of radionics equipment to British and European researchers and physicians.

The most influential of the second generation of British radionics researchers was the husband-and-wife team of Marjorie and George de la Warr. (That's Marjorie on the right, working with one of their radionics machines.) George was an engineer who became fascinated with radionics between the two world wars. At that time nearly all radionics gear was manufactured in the United States, and getting the necessary equipment overseas was expensive. De la Warr's response was to contact Ruth Drown and get a license to build machines using her design in Britain. De La Warr Laboratories soon became a major supplier of radionics equipment to British and European researchers and physicians.  The de la Warrs -- that's George on the left -- also went to work with the strangest of Ruth Drown's inventions, a camera that apparently took pictures at a distance through radionics. They scored some eerie hits: for example, using a drop of blood from a cancer patient, they produced a photo showing a tumor in his brain. When the patient died and was autopsied, the location and size of the tumor turned out to be correct. (This was long before CAT and MRI scans, remember.)

The de la Warrs -- that's George on the left -- also went to work with the strangest of Ruth Drown's inventions, a camera that apparently took pictures at a distance through radionics. They scored some eerie hits: for example, using a drop of blood from a cancer patient, they produced a photo showing a tumor in his brain. When the patient died and was autopsied, the location and size of the tumor turned out to be correct. (This was long before CAT and MRI scans, remember.)  The de la Warrs inspired many other British radionics practitioners, and helped launch a wave of innovation in the field. Among the leading figures in the movement were Malcolm Rae and Darrell Butcher, who devised radionics machines of their own designs and did extensive experimental work with them. Perhaps the most revolutionary work in the field, however, was done by Dr. David Tansley, a chiropractor who became interested in radionics in the 1960s. Tansley -- that's him on the right -- had an encyclopedic knowledge of esoteric philosophy and Asian mystical traditions, and he seems to have been the first person to explore the interface between radionics and these older ways of understanding and working with the life force. His many books on radionics helped guide other researchers and practitioners into a broader sense of what they were working with.

The de la Warrs inspired many other British radionics practitioners, and helped launch a wave of innovation in the field. Among the leading figures in the movement were Malcolm Rae and Darrell Butcher, who devised radionics machines of their own designs and did extensive experimental work with them. Perhaps the most revolutionary work in the field, however, was done by Dr. David Tansley, a chiropractor who became interested in radionics in the 1960s. Tansley -- that's him on the right -- had an encyclopedic knowledge of esoteric philosophy and Asian mystical traditions, and he seems to have been the first person to explore the interface between radionics and these older ways of understanding and working with the life force. His many books on radionics helped guide other researchers and practitioners into a broader sense of what they were working with.  We ended last week's post in this sequence with Wilhelm Reich safely ensconced in the United States, constructing his first orgone accumulators using alternating layers of conductive and insulative materials. He was by this time certain that he'd broken through into an entirely new field of scientific research, and that orgone was a reality -- an energy closely related to biological life and health, which bridged the gap between psychology and physiology. It was a busy time for him; he was teaching classes at Manhattan's New School for Social Research, training physicians in the techniques he'd already devised, getting his books translated into English, and pursuing further researches into orgone.

We ended last week's post in this sequence with Wilhelm Reich safely ensconced in the United States, constructing his first orgone accumulators using alternating layers of conductive and insulative materials. He was by this time certain that he'd broken through into an entirely new field of scientific research, and that orgone was a reality -- an energy closely related to biological life and health, which bridged the gap between psychology and physiology. It was a busy time for him; he was teaching classes at Manhattan's New School for Social Research, training physicians in the techniques he'd already devised, getting his books translated into English, and pursuing further researches into orgone.  I'm not sure how many of my readers realize that today's sky-high rates of cancer are a very recent phenomenon. In the 19th century, cancer was an uncommon disease, mostly found in old people -- childhood cancers were so rare that individual cases were written up in medical journals. That started to change between the two world wars, but it was after the end of the Second World War that cancer rates soared and cancer became the #2 cause of death in the United States. Readers of my generation and older will recall the flurry of books and movies in the 1960s about young adults dying of cancer -- Love Story, Brian's Song, Sunshine, and so on through a very long list. Those made such a splash because young adults dying of cancer was a new and shocking thing at that time.

I'm not sure how many of my readers realize that today's sky-high rates of cancer are a very recent phenomenon. In the 19th century, cancer was an uncommon disease, mostly found in old people -- childhood cancers were so rare that individual cases were written up in medical journals. That started to change between the two world wars, but it was after the end of the Second World War that cancer rates soared and cancer became the #2 cause of death in the United States. Readers of my generation and older will recall the flurry of books and movies in the 1960s about young adults dying of cancer -- Love Story, Brian's Song, Sunshine, and so on through a very long list. Those made such a splash because young adults dying of cancer was a new and shocking thing at that time.  Reich was completely unaware of this. He was caught up in his research, trying to push the boundaries of his new science of orgonomics. He experimented with the effects of orgone accumulators on radioactive material and nearly ended up with a disaster on his hands -- the result was a devitalized form of orgone that Reich named DOR, "deadly orgone radiation." He found by accident that orgone directed from an accumulator toward the sky appeared to cause changes in weather, and developed a device -- the "Cloudbuster" -- which was tested successfully in drought conditions in Arizona and Maine. He built a new home and laboratory in Rangeley, Maine, where he pursued his work.

Reich was completely unaware of this. He was caught up in his research, trying to push the boundaries of his new science of orgonomics. He experimented with the effects of orgone accumulators on radioactive material and nearly ended up with a disaster on his hands -- the result was a devitalized form of orgone that Reich named DOR, "deadly orgone radiation." He found by accident that orgone directed from an accumulator toward the sky appeared to cause changes in weather, and developed a device -- the "Cloudbuster" -- which was tested successfully in drought conditions in Arizona and Maine. He built a new home and laboratory in Rangeley, Maine, where he pursued his work. One of the things that makes the history of modern etheric technologies complex is that there isn't a nice straightforward sequence of researchers, each of whom picks up where the previous one left off. More precisely, such a sequence exists -- the development of radionics from Albert Abrams through Ruth Drown to George and Marjorie de la Warr, T. Galen Hieronymus, and David Tansley, among others -- but other researchers such as Leon Eeman and Walter Kilner have stumbled across the same realm of etheric energy and explored it in their own unique ways, coming up with their own terminology and techniques. The subject of this week's post is far and away the most colorful and controversial of these figures: that astonishing force of nature, Wilhelm Reich.

One of the things that makes the history of modern etheric technologies complex is that there isn't a nice straightforward sequence of researchers, each of whom picks up where the previous one left off. More precisely, such a sequence exists -- the development of radionics from Albert Abrams through Ruth Drown to George and Marjorie de la Warr, T. Galen Hieronymus, and David Tansley, among others -- but other researchers such as Leon Eeman and Walter Kilner have stumbled across the same realm of etheric energy and explored it in their own unique ways, coming up with their own terminology and techniques. The subject of this week's post is far and away the most colorful and controversial of these figures: that astonishing force of nature, Wilhelm Reich.  In 1939, just before war broke out, he relocated to the United States and continued his researches on the mechanism of the orgasm. His theory while he was in Norway was that the orgasm was an electrochemical release of energy, but around the time he arrived in the United States his experiments convinced him that he had discovered an energy unknown to science, which behaved a little like electricity but was closely linked to biological life. (Sound familiar?) He called this energy "orgone."

In 1939, just before war broke out, he relocated to the United States and continued his researches on the mechanism of the orgasm. His theory while he was in Norway was that the orgasm was an electrochemical release of energy, but around the time he arrived in the United States his experiments convinced him that he had discovered an energy unknown to science, which behaved a little like electricity but was closely linked to biological life. (Sound familiar?) He called this energy "orgone."  Despite the usual pushback from the medical profession, the work of Dr. Albert Abrams -- which was discussed in

Despite the usual pushback from the medical profession, the work of Dr. Albert Abrams -- which was discussed in  Some of her innovations turned out to be crucial for the evolution of radionics -- a term which she invented, by the way. Along with the recognition that some force distinct from radio waves and electricity was responsible for radionics cures, she pioneered the "stick pad," a plate of glass or plexiglass used by radionics machine operators to gauge the flow of the unknown force through the machine, and she began the systematic collection of "rates" -- settings on radionics machines -- which are specific to illnesses, organs, and other factors. These became standard elements of radionics during her lifetime and remain common today.

Some of her innovations turned out to be crucial for the evolution of radionics -- a term which she invented, by the way. Along with the recognition that some force distinct from radio waves and electricity was responsible for radionics cures, she pioneered the "stick pad," a plate of glass or plexiglass used by radionics machine operators to gauge the flow of the unknown force through the machine, and she began the systematic collection of "rates" -- settings on radionics machines -- which are specific to illnesses, organs, and other factors. These became standard elements of radionics during her lifetime and remain common today.  Yes, there was a trial. In the wake of the Second World War, as the American Medical Association and the pharmaceutical industry tightened their grip on health and healing in the United States, alternative medical practitioners of all kinds came in for increasing persecution under laws designed to defend the medical monopoly. In 1950, at the behest of the AMA, federal authorities brought charges against Drown. Most of the evidence she offered in her own defense -- evidence that her methods worked, and that she had successfully diagnosed and treated thousands of patients -- was excluded from her trial. She was accordingly convicted of interstate fraud for shipping one of her machines across a state line and served a brief prison sentence. Still more legal charges were pending against her when she died in 1965.

Yes, there was a trial. In the wake of the Second World War, as the American Medical Association and the pharmaceutical industry tightened their grip on health and healing in the United States, alternative medical practitioners of all kinds came in for increasing persecution under laws designed to defend the medical monopoly. In 1950, at the behest of the AMA, federal authorities brought charges against Drown. Most of the evidence she offered in her own defense -- evidence that her methods worked, and that she had successfully diagnosed and treated thousands of patients -- was excluded from her trial. She was accordingly convicted of interstate fraud for shipping one of her machines across a state line and served a brief prison sentence. Still more legal charges were pending against her when she died in 1965.  The first third of the twentieth century, when Albert Abrams was perfecting his machines and Leon Eeman was experimenting with biocircuits, was in many ways the golden age of etheric technology. The culture of independent scientific research was still in full flower, old-fashioned occult philosophy was still a major cultural force, and there were plenty of researchers in and out of the scientific community who were willing to buck the materalist dogma of the time and explore the Unseen using the tools of scientific research. One of the most prestigious figures in that movement was Dr. Walter Kilner.

The first third of the twentieth century, when Albert Abrams was perfecting his machines and Leon Eeman was experimenting with biocircuits, was in many ways the golden age of etheric technology. The culture of independent scientific research was still in full flower, old-fashioned occult philosophy was still a major cultural force, and there were plenty of researchers in and out of the scientific community who were willing to buck the materalist dogma of the time and explore the Unseen using the tools of scientific research. One of the most prestigious figures in that movement was Dr. Walter Kilner.  The standard optical filter in his time consisted of alcohol and dye held between two disks of glass, surrounded by a metal frame. That allowed Kilner to experiment with a wide range of dyes, and that led him in turn to an unexpected discovery. If someone spent several minutes looking through a filter that used dicyanin, a common dark blue dye, and then went into a dim room, that person's eyes would be temporarily sensitized to the aura. Repeat the same experience several times and the sensitization became permanent. The technology that resulted from this was simple: a set of goggles that had dicyanin filters in place of lenses, and could be used quite easily by experimenters to sensitize their own eyes and those of experimental subjects.

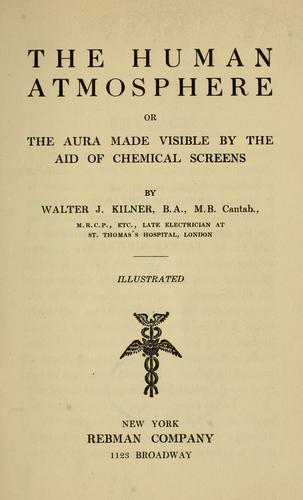

The standard optical filter in his time consisted of alcohol and dye held between two disks of glass, surrounded by a metal frame. That allowed Kilner to experiment with a wide range of dyes, and that led him in turn to an unexpected discovery. If someone spent several minutes looking through a filter that used dicyanin, a common dark blue dye, and then went into a dim room, that person's eyes would be temporarily sensitized to the aura. Repeat the same experience several times and the sensitization became permanent. The technology that resulted from this was simple: a set of goggles that had dicyanin filters in place of lenses, and could be used quite easily by experimenters to sensitize their own eyes and those of experimental subjects.  Kilner published a book on the subject, The Human Atmosphere, in 1911, which you can download for free

Kilner published a book on the subject, The Human Atmosphere, in 1911, which you can download for free  During the years when Dr. Albert Abrams was busy laying the foundations of radionics, other researchers were pursuing their own investigations into the life force. One of them was Leon Eeman, shown on the left. Born in Belgium, he became a British subject and served in the Royal Air Force during the First World War. An airplane crash left him so seriously wounded that he was hospitalized for two years, and the physicians told him he had no hope of making a full recovery.

During the years when Dr. Albert Abrams was busy laying the foundations of radionics, other researchers were pursuing their own investigations into the life force. One of them was Leon Eeman, shown on the left. Born in Belgium, he became a British subject and served in the Royal Air Force during the First World War. An airplane crash left him so seriously wounded that he was hospitalized for two years, and the physicians told him he had no hope of making a full recovery.  Of all the etheric technologies we'll be discussing in this series of entries, the Eeman biocircuit is the simplest. In its most basic form it consists of two copper mesh screens connected by wires to two short dowels covered with copper foil. The user lies down on his or her back, with one screen under the head and one under the base of the spine, takes hold of the handles, and crosses the legs at the ankles. The user then relaxes for thirty minutes or so. Eeman found that setting up a relaxation circuit once a day led to significant improvements in health and well-being. My experience, on the occasions when I have had the chance to use a set of Eeman screens, is that he was right: the effect is gentle but definite, and resembles nothing so much as what happens in healing by laying on of hands.

Of all the etheric technologies we'll be discussing in this series of entries, the Eeman biocircuit is the simplest. In its most basic form it consists of two copper mesh screens connected by wires to two short dowels covered with copper foil. The user lies down on his or her back, with one screen under the head and one under the base of the spine, takes hold of the handles, and crosses the legs at the ankles. The user then relaxes for thirty minutes or so. Eeman found that setting up a relaxation circuit once a day led to significant improvements in health and well-being. My experience, on the occasions when I have had the chance to use a set of Eeman screens, is that he was right: the effect is gentle but definite, and resembles nothing so much as what happens in healing by laying on of hands.  Central to Eeman's approach was the idea that the unknown healing force he was using -- he called it, sensibly enough, the X force -- was bipolar, like magnetism. Where a magnet has two poles, the human body has several, as shown on the left. Bringing the poles into contact with one another, directly or by way of wires, appeared to bring about energy flow with definite effects on the body.

Central to Eeman's approach was the idea that the unknown healing force he was using -- he called it, sensibly enough, the X force -- was bipolar, like magnetism. Where a magnet has two poles, the human body has several, as shown on the left. Bringing the poles into contact with one another, directly or by way of wires, appeared to bring about energy flow with definite effects on the body.  The transition from the investigations of Mesmer and Reichenbach to contemporary radionics began with Dr. Albert Abrams, the gentleman on the left. Born in San Francisco in 1863, he began his medical studies at a local college, got his M.D., then -- in the usual fashion in those days -- went abroad to get a second degree, which he received from the prestigious Heidelberg University medical school in Germany in 1882. After further study at medical schools in London, Berlin, Vienna, and Paris, he returned to San Francisco and hung out his shingle. He became one of the most respected neurologists on the west coast, taught for fourteen years at the Cooper College medical school, and was elected vice-president of the California State Medical Society in 1889.

The transition from the investigations of Mesmer and Reichenbach to contemporary radionics began with Dr. Albert Abrams, the gentleman on the left. Born in San Francisco in 1863, he began his medical studies at a local college, got his M.D., then -- in the usual fashion in those days -- went abroad to get a second degree, which he received from the prestigious Heidelberg University medical school in Germany in 1882. After further study at medical schools in London, Berlin, Vienna, and Paris, he returned to San Francisco and hung out his shingle. He became one of the most respected neurologists on the west coast, taught for fourteen years at the Cooper College medical school, and was elected vice-president of the California State Medical Society in 1889.  So the learned and respected Dr. Abrams pursued a series of research projects in his spare time, like many of his colleagues. He was very interested in percussion of the abdomen as a diagnostic tool, and found that under certain very specific conditions -- the patient had to be standing, and facing a particular direction -- percussion would accurately diagnose a range of diseases. The one problem was that patients who were very sick couldn't stand up for the prolonged session of percussion Abrams used. So, drawing on the theory that nerve impulses were electrical in nature -- standard medical opinion in his time -- Abrams decided to see if he could hook up a patient with a healthy volunteer using copper headbands, a copper plate under the feet, and wires connecting them. He did, and he found he could get the same diagnostic reactions in the volunteer.

So the learned and respected Dr. Abrams pursued a series of research projects in his spare time, like many of his colleagues. He was very interested in percussion of the abdomen as a diagnostic tool, and found that under certain very specific conditions -- the patient had to be standing, and facing a particular direction -- percussion would accurately diagnose a range of diseases. The one problem was that patients who were very sick couldn't stand up for the prolonged session of percussion Abrams used. So, drawing on the theory that nerve impulses were electrical in nature -- standard medical opinion in his time -- Abrams decided to see if he could hook up a patient with a healthy volunteer using copper headbands, a copper plate under the feet, and wires connecting them. He did, and he found he could get the same diagnostic reactions in the volunteer.  This was fascinating, and it became even more so when he hooked up rheostats (variable resistors) into the wires in an attempt to fine-tune the reaction. He found quite reliably that certain rheostat settings made the percussive response much louder, but only if the patient had some specific illness. He proceeded to run more tests and build more machines, and got stranger and stranger results. He found, for example, that he could take a blood sample from a patient, hook it up to his machines, and get a diagnostic reading from the volunteer's abdomen.

This was fascinating, and it became even more so when he hooked up rheostats (variable resistors) into the wires in an attempt to fine-tune the reaction. He found quite reliably that certain rheostat settings made the percussive response much louder, but only if the patient had some specific illness. He proceeded to run more tests and build more machines, and got stranger and stranger results. He found, for example, that he could take a blood sample from a patient, hook it up to his machines, and get a diagnostic reading from the volunteer's abdomen.  He also started looking into possibilities for treatment using the same principle. The idea of using low-power radio waves for healing was common in the medical scene in those days -- one such method, short-wave diathermy, had already shown considerable promise -- and so he set out to build machines that would use his resistance settings to beam healing radio waves into patients. The sort of giddy mad-scientist hardware shown above soon gave way to elegant Victorian devices like the one on the right -- the first radionics machines, though the term hadn't been invented yet.

He also started looking into possibilities for treatment using the same principle. The idea of using low-power radio waves for healing was common in the medical scene in those days -- one such method, short-wave diathermy, had already shown considerable promise -- and so he set out to build machines that would use his resistance settings to beam healing radio waves into patients. The sort of giddy mad-scientist hardware shown above soon gave way to elegant Victorian devices like the one on the right -- the first radionics machines, though the term hadn't been invented yet.  Of course, being the experienced and capable scientist that he was, he wrote up his experiments and their results in great detail and published them. (That's the English translation on the right.) And the scientific community -- did it say, "Wow, here's something new from von Reichenbach, he's always worth reading, let's check it out"? Not a chance. With a few noble exceptions, they did what scientists almost always do when confronted with evidence for the life force: they pulled a James Randi -- that is, they launched a flurry of ad hominem attacks and then ran experiments that changed crucial variables, and when those didn't get the same results (quelle choque!), announced a failure to replicate. It's a familiar song and dance, and it was already well practiced by von Reichenbach's time.

Of course, being the experienced and capable scientist that he was, he wrote up his experiments and their results in great detail and published them. (That's the English translation on the right.) And the scientific community -- did it say, "Wow, here's something new from von Reichenbach, he's always worth reading, let's check it out"? Not a chance. With a few noble exceptions, they did what scientists almost always do when confronted with evidence for the life force: they pulled a James Randi -- that is, they launched a flurry of ad hominem attacks and then ran experiments that changed crucial variables, and when those didn't get the same results (quelle choque!), announced a failure to replicate. It's a familiar song and dance, and it was already well practiced by von Reichenbach's time.  A post I made here

A post I made here  Mesmer was a medical doctor from Austria -- that's him on the right. Like a lot of physicians with scientific interests in his day, he experimented with the medical applications of magnetism, but his experiments convinced him that there was a different force -- like magnetism in some ways, like electricity in others -- that was generated by living things. It obeyed straightforward physical laws, comparable to those that govern the behavior of electricity and light; it could be stored, directed, and made to flow along conductive materials -- and it could heal. He called it "animal magnetism." His experiments in Vienna were successful enough to win him a very substantial clientele and make him enough money that he could hire a talented kid named Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to write a one-act operetta for a garden party. (Bastian und Bastienne, the operetta, was Mozart's first operatic work, written when he was twelve.)

Mesmer was a medical doctor from Austria -- that's him on the right. Like a lot of physicians with scientific interests in his day, he experimented with the medical applications of magnetism, but his experiments convinced him that there was a different force -- like magnetism in some ways, like electricity in others -- that was generated by living things. It obeyed straightforward physical laws, comparable to those that govern the behavior of electricity and light; it could be stored, directed, and made to flow along conductive materials -- and it could heal. He called it "animal magnetism." His experiments in Vienna were successful enough to win him a very substantial clientele and make him enough money that he could hire a talented kid named Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to write a one-act operetta for a garden party. (Bastian und Bastienne, the operetta, was Mozart's first operatic work, written when he was twelve.) The baquet shown above is a very straightforward device, and the diagram to the left shows how it worked. The heart of it was a large Leyden jar. Leyden jar? That's called a capacitor nowadays; it's a glass jar with a layer of foil inside and outside, which was used in electrical research in Mesmer's time as a way to store electric charges. In the baquet, the Leyden jar was surrounded by a thick layer of insulation -- Mesmer used straw -- with bottles of water interspersed with the insulation. At intervals, metal rods descended through the insulation well away from the outside of the Leyden jar, and to the top of each of the rods was fixed a jointed rod that patients held when they were being treated. The baquet was charged by Mesmer himself -- I have not been able to track down the exact method, but it probably involved breathing and concentration, while Mesmer put one hand on the central "double bell" and the other on the ring of metal to which the rods were connected. The baquet may also have gathered animal magnetism on its own account -- as we'll see when we get to Wilhelm Reich, there were fascinating parallels between his technology and Mesmer's.

The baquet shown above is a very straightforward device, and the diagram to the left shows how it worked. The heart of it was a large Leyden jar. Leyden jar? That's called a capacitor nowadays; it's a glass jar with a layer of foil inside and outside, which was used in electrical research in Mesmer's time as a way to store electric charges. In the baquet, the Leyden jar was surrounded by a thick layer of insulation -- Mesmer used straw -- with bottles of water interspersed with the insulation. At intervals, metal rods descended through the insulation well away from the outside of the Leyden jar, and to the top of each of the rods was fixed a jointed rod that patients held when they were being treated. The baquet was charged by Mesmer himself -- I have not been able to track down the exact method, but it probably involved breathing and concentration, while Mesmer put one hand on the central "double bell" and the other on the ring of metal to which the rods were connected. The baquet may also have gathered animal magnetism on its own account -- as we'll see when we get to Wilhelm Reich, there were fascinating parallels between his technology and Mesmer's. .png?bwg=1608078185) I had occasion earlier today to check up on the state of the art in radionics. Radionics? It's a weird hybrid of sorcery and technology, in which a variety of electro-etheric devices such as the Hieronymus Machine (an example is on the left) are used in place of the typical medieval technology of wands and star-spangled robes. Rather more than a decade ago I built a Hieronymus machine, collected all the necessary information to use it, and spent a while getting a good sense of its potentials for spirituality, divination, magic, and healing; I don't do a lot with it any more, but I've still got my endearingly clumky homebrew machine, and get good results with it when I do use it.

I had occasion earlier today to check up on the state of the art in radionics. Radionics? It's a weird hybrid of sorcery and technology, in which a variety of electro-etheric devices such as the Hieronymus Machine (an example is on the left) are used in place of the typical medieval technology of wands and star-spangled robes. Rather more than a decade ago I built a Hieronymus machine, collected all the necessary information to use it, and spent a while getting a good sense of its potentials for spirituality, divination, magic, and healing; I don't do a lot with it any more, but I've still got my endearingly clumky homebrew machine, and get good results with it when I do use it.  I'm delighted to report that The UFO Chronicles, the updated, revised, and considerably expanded new edition of my book on the UFO phenomenon, will be released Monday from Aeon Books. This is not your ordinary UFO book. Since 1947, with embarrassingly few exceptions, the entire subject has been frozen in a false dichotomy between "UFO believers" (meaning people whose default opinion about any unknown object in the sky is that it must be an alien spacecraft) and "UFO skeptics" (meaning people whose default opinion about any unknown object in the sky is that was never there in the first place).

I'm delighted to report that The UFO Chronicles, the updated, revised, and considerably expanded new edition of my book on the UFO phenomenon, will be released Monday from Aeon Books. This is not your ordinary UFO book. Since 1947, with embarrassingly few exceptions, the entire subject has been frozen in a false dichotomy between "UFO believers" (meaning people whose default opinion about any unknown object in the sky is that it must be an alien spacecraft) and "UFO skeptics" (meaning people whose default opinion about any unknown object in the sky is that was never there in the first place).